THE TUSKEGEE AIRMEN STORY: POSTWAR SERVICE

Although the record of the Tuskegee Airmen and other Black units in World War II was the most important element in convincing the United States Air Force leaders of 1947 and 1948 that the Air Force would fight better integrated than segregated, the fact that the Tuskegee Airmen had fought brilliantly in Europe was not generally known outside of the Air Force, and was certainly not well known even in that service.

Complicating the publicizing of the Tuskegee Airmen story, moreover, was the general bigotry of the Army Air Force's leadership. The men in the War Department and the major command positions in the Air Corps had not wanted the Tuskegee Airmen in the Army Air Forces in the first place, and were first skeptical and then reluctant to believe in their successes. The men at the top were so bigoted, in fact, that they supported Selway and Hunter as those two men conspired to insult and degrade the Black officers of the 477th even though they were sworn to work efficiently and effectively to prosecute the war.

The bigotry did not end with Japan's surrender. Segregation and discrimination continued, and the War Department had difficulty finding an adequate station for the 477th which had to be moved from Godman Field because of that airfield's manifest inadequacies. Eventually, over the objections of the editorial writers of Columbus, Ohio's leading newspaper, the 477th was moved to Lockbourne Army Air Field, Ohio, in March 1946.

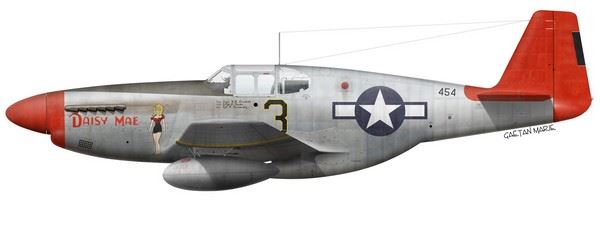

At Lockbourne, now called Rickenbacker Air Force Base, the Group flew proficiency and tactical missions, participated in war games and worked hard to maintain their combat edge. In the summer of 1947, just before the Air Force became independent, the 477th became an all-fighter unit, redesignated the 332nd Fighter Group, and later the 332nd Fighter Wing.

In the next six months, the 332nd Fighter Wing took part in firepower demonstrations at Eglin Field, Florida, and at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina.

In 1948 and 1949, the unit, along with the other fifty-four wings of the US Air Force, participated in large-scale exercises, taking and passing operational readiness inspections, and winning an Air Force gunnery meet in May 1949. The fact is, that despite segregation, the Air Force's Tactical Air Command tasked the 332nd to fly just as it tasked all of the other fighter outfits in the command.

This in fact, had been the case since the unit's tour in Italy. The 332nd was a fighter outfit as all others and was tasked to perform as all others, and could be counted on as the others. This fact gave powerful justification and motivation for officials in the military, to integrate the Air Force. Segregation was a terrible burden, both to the men who suffered under it and to the Air Force itself, and those who had to lead and manage the Air Force knew it. They knew that segregation was discrimination and that it led to low morale and even to rioting. The Air Force also had difficulty staffing units because of segregation. The 332nd, for example, was a fine flying outfit, but was short of pilots at the same time that other wings had a surplus of pilots, but none of these could be sent to the 332nd because of existing racial policies.

Like-wise, the 332nd had surplus navigators and navigator-bombardiers left over from the old B-25 days, when Strategic Air Command was in need of those men, but they could not be utilized there because the Strategic Air Command was all white. There were similar stories to tell regarding enlisted men in various specialties.

The basis of segregation and discrimination that it provoked was rooted in the notion of racial inferiority. The antidote to this poison was the fact that the record of the Tuskegee Airmen was sufficient to reject that notion.

When the Air Force became independent of the Army in 1947, the Air Force Chief of Personnel, Lieutenant General Idwal Edwards, decided not to be bound by the Army segregation policy. He sponsored a study to investigate the reasons and justification, if any, for racial segregation. Edwards himself was convinced of the individual flying ability of many of the Tuskegee Airmen and was eager to unburden himself of the weight of a segregated service. Edwards was a White Air Force leader who was willing to fairly evaluate the contributions of Black personnel for the benefit of the service. The study supported Edwards' point of view that individual Blacks with equal aptitude and with equal training performed as well as Whites, thus undermining the foundation of segregation. The Tuskegee Airmen had provided the prima facie evidence.

In April 1948, the Chief of Staff of the Air Force, General Carl Spaatz, announced his intention to eliminate segregation. Undersecretary of the Air Force, Eugene Zuckert, announced the same intention later in the month, saying also that "the Air Force accepts no doctrine of superiority or inferiority." With his leaders behind him, General Edwards proceeded to draw up the plans to integrate the Air Force. It is noted, therefore, that the Air Force's announcement to the public that it intended to integrate preceded President Harry S. Truman Executive Order 9981 of July 1948. Air Force racial integration put pressure on the other services to follow suit, and of course it improved the Air Force by opening the manpower pool to that ten percent of the American population that is Black. The Army integrated beginning in 1951 on the same basis as the Air Force: the need for improved fighting capability during the Korean conflict. Subsequently, the Armed Forces became the most thoroughly integrated segment of American society, and they still are.

It was the Armed Forces integration that helped inspire the rest of the country to change its racial pattern. We now have an improved America—a long way from where it can and should be, but a long way from where it was because the Armed Forces were the first to recognize that improvement would come from supporting racial justice. Thus, the foundation for this move toward integration was the fighting example of the Tuskegee Airmen who proved that they could overcome adversity to fly and fight with the best of pilots from any nation in the modern world.

EAST COAST CHAPTER 120 Waterfront Street, Ste 420-2189 National Harbor, MD 20745 | * indicates required

|